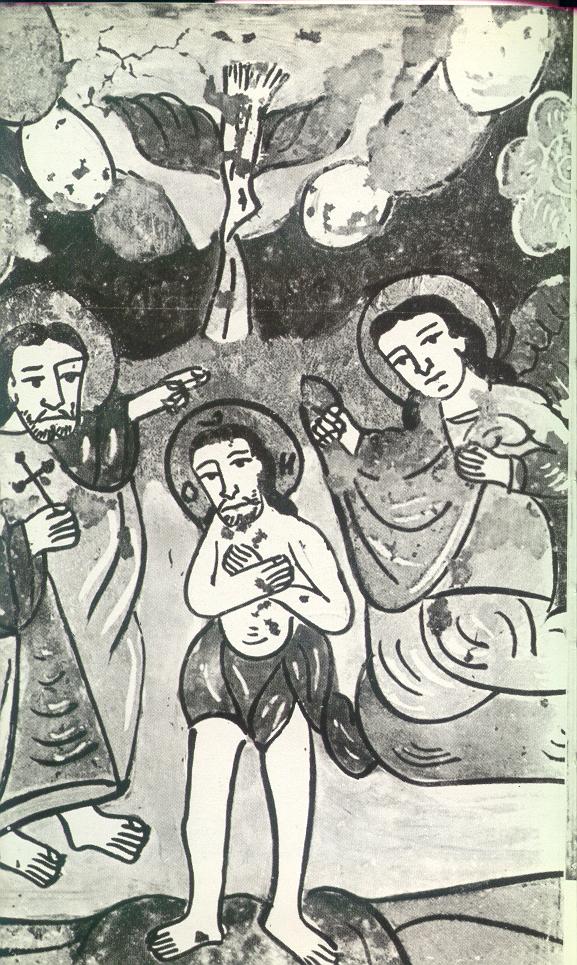

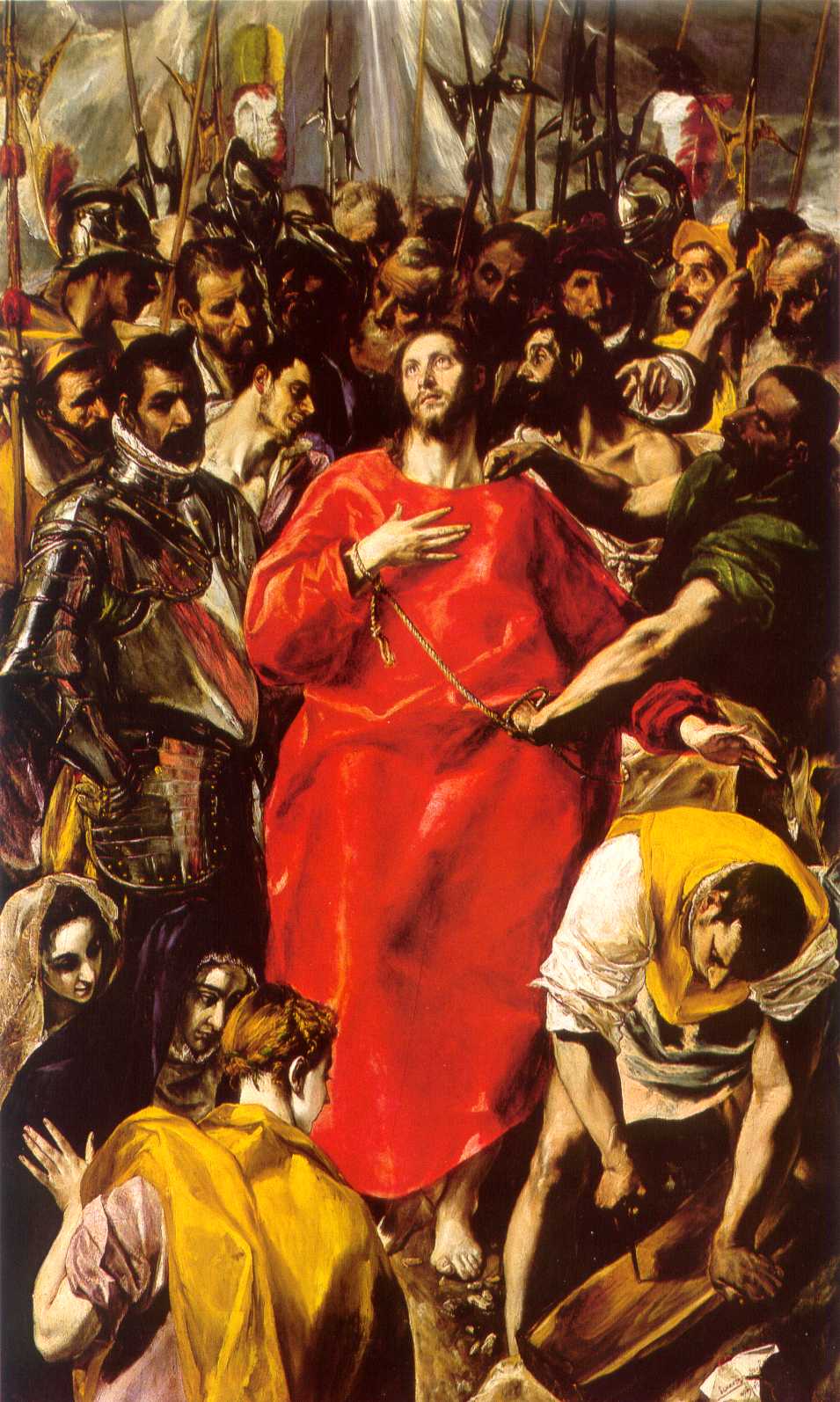

Here is one of the most spread atittudes in the images of the European art. Although the chosen images belong to different era and spaces, the attitude keeps the same signification. The arms crossed over the chest show that the character is praying. It offers itself the reception of the sacred message that has been sent to it. The meaning is the same in fig. 1 - where the character is an adoring figure presenting itself to the gods, and in fig. 2, 3. The last two figures give a Christian form to the attitude. Christ is strengthen the baptism by the same gesture (fig.2) and is pacified with his mission (fig.3). We choose this example for their distance in time (aprox. 7000 b.Ch.; Century XIX; 1579) and because they belong to spiritual different spaces (neolithic Crete, orthodox Transilvania, catholic Spain).

Fig. 1 - Statue of man - cca. 7000 b. Chr., Crete |

Fig. 2 - The Baptizing of Christ - XIX century, Nicula Monastery, Transilvania |

Fig. 3 - El Greco, "El Espolio"- 1579, Spain |

|

Annex 2

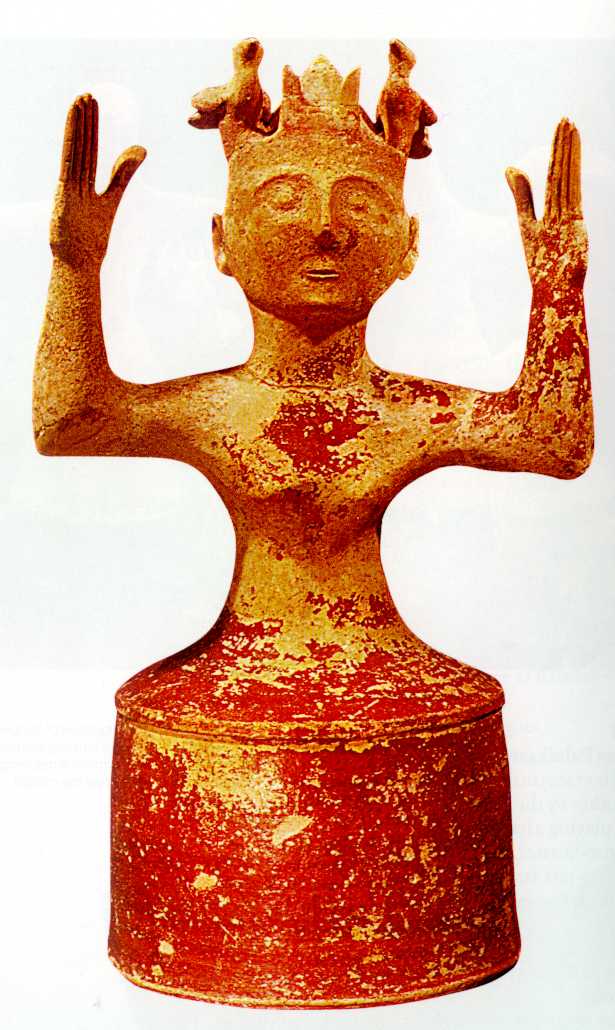

Here is presented another one of the most used gestures. The open atittude, with arms raised horizontally and forearms with palms of hands open raised vertically, transforms the body into a receptor. It actions canalizing cosmice energies to the center of the being. It is obvious this sense (of receiving) in all four images : the first two dating from the period of the New Palace from Crete, in the Catalan wood panting - St. Cyriacus filling himself with energy while is martirized; in the figure of the mother of St. Francisc receiving the news of the saint's birth from a pilgrim. One may observe the same atittude in the figure of Virgin Mary - Orant, in the Bizantyne painting.

Annex 3

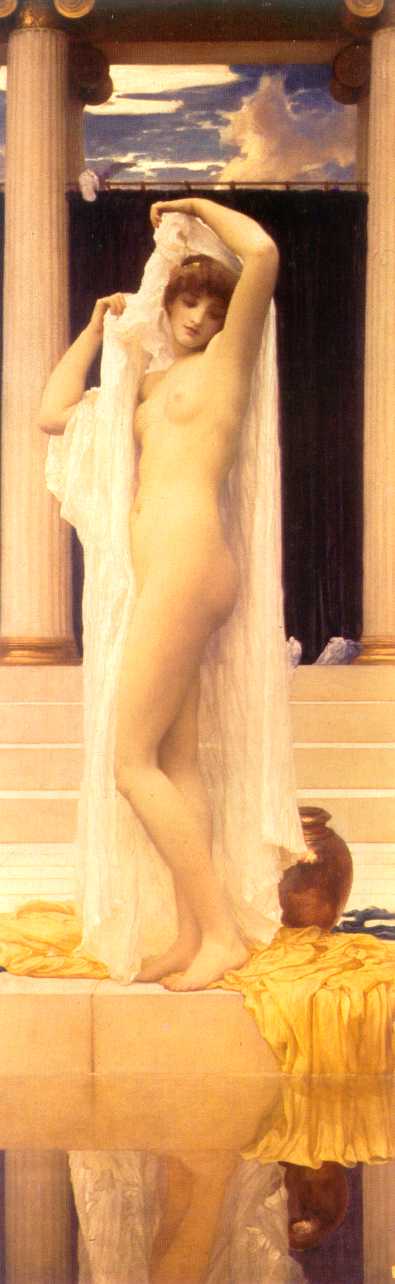

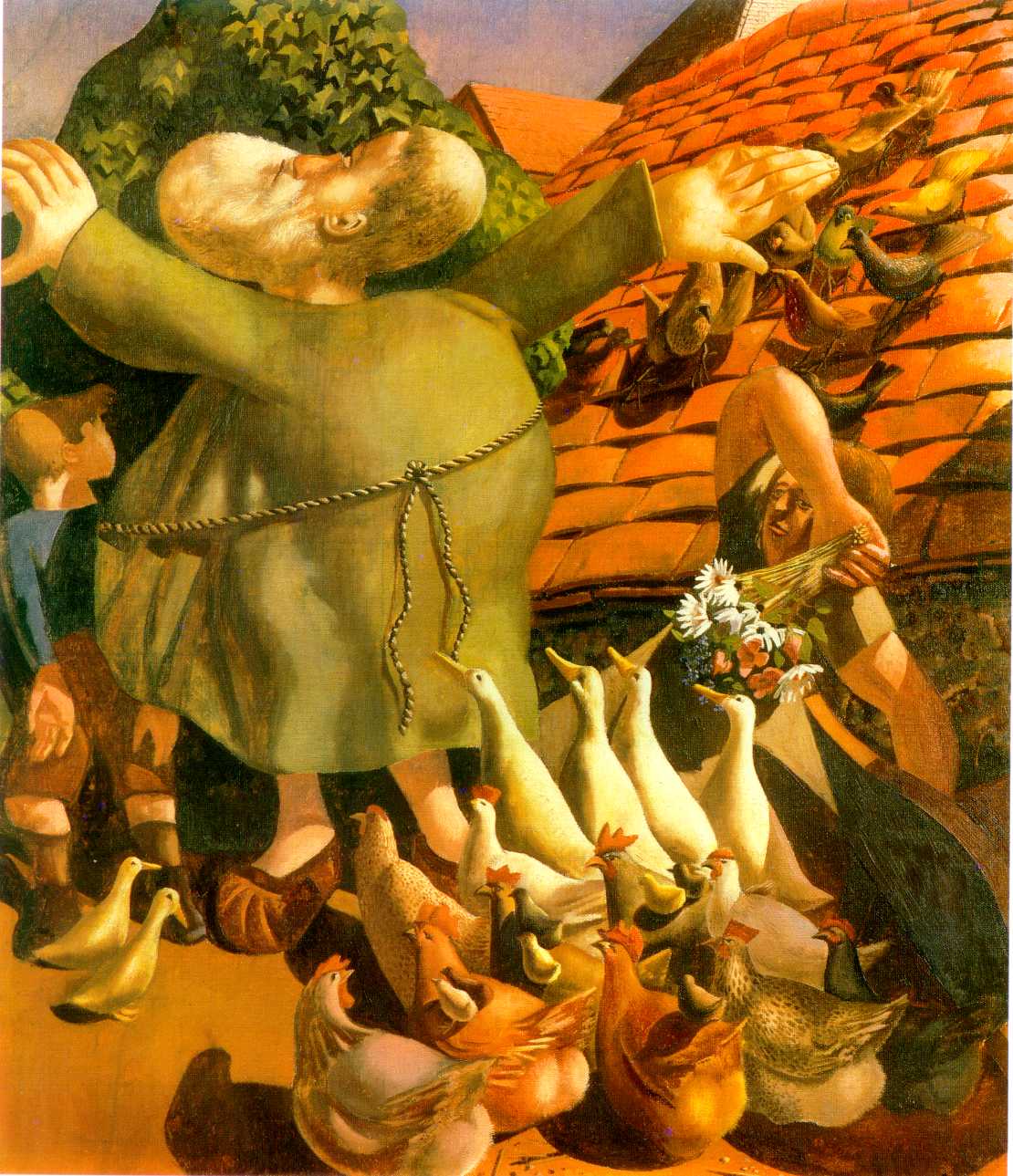

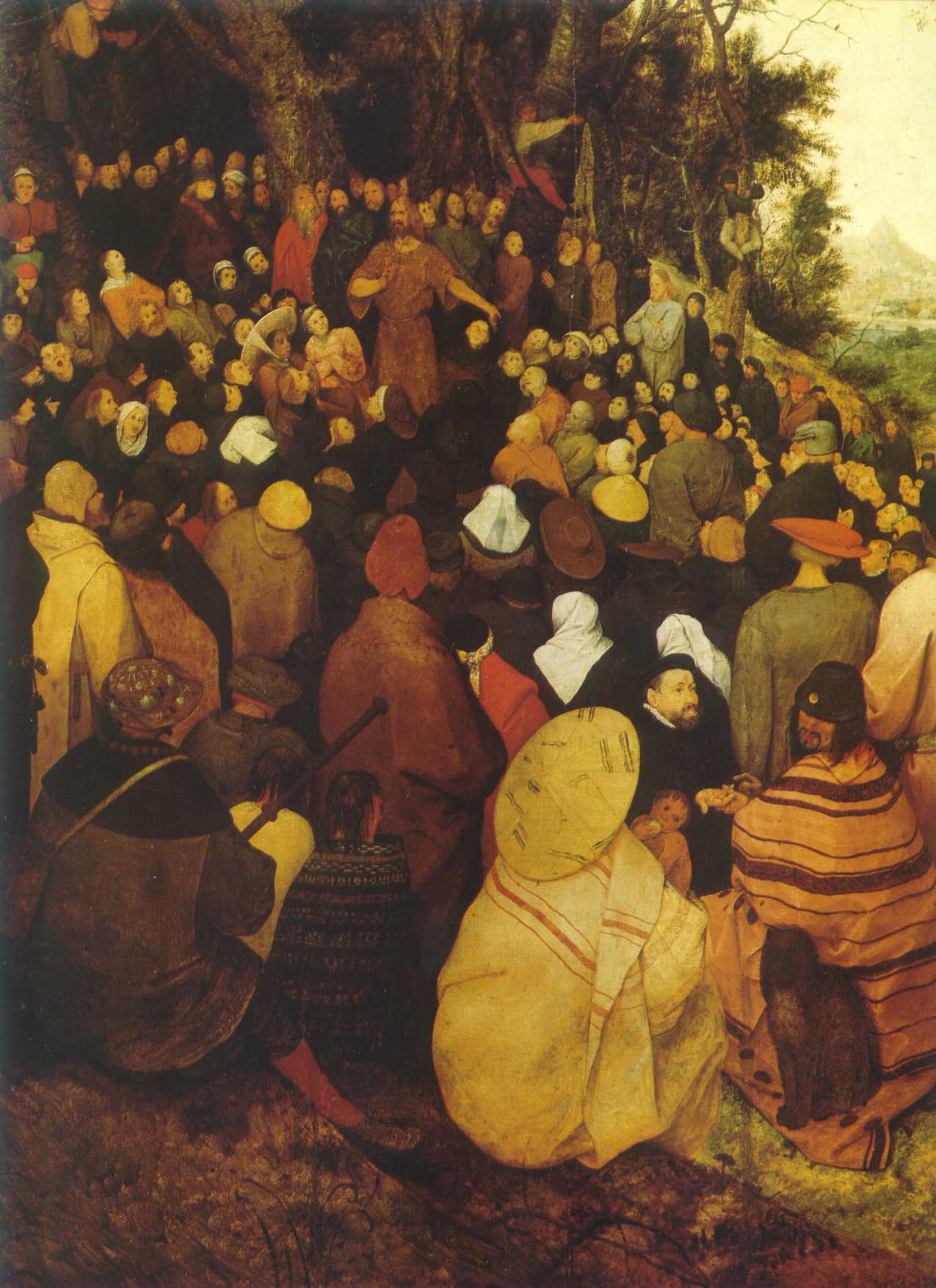

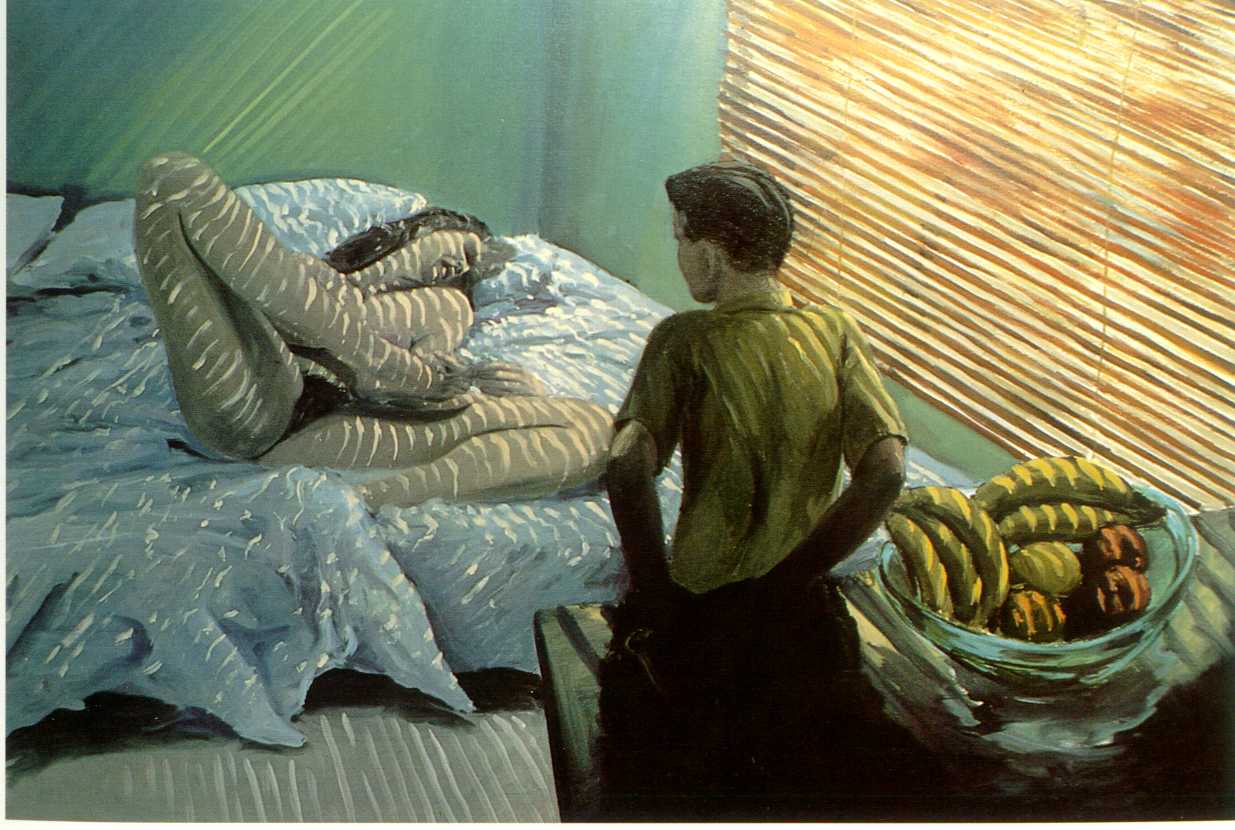

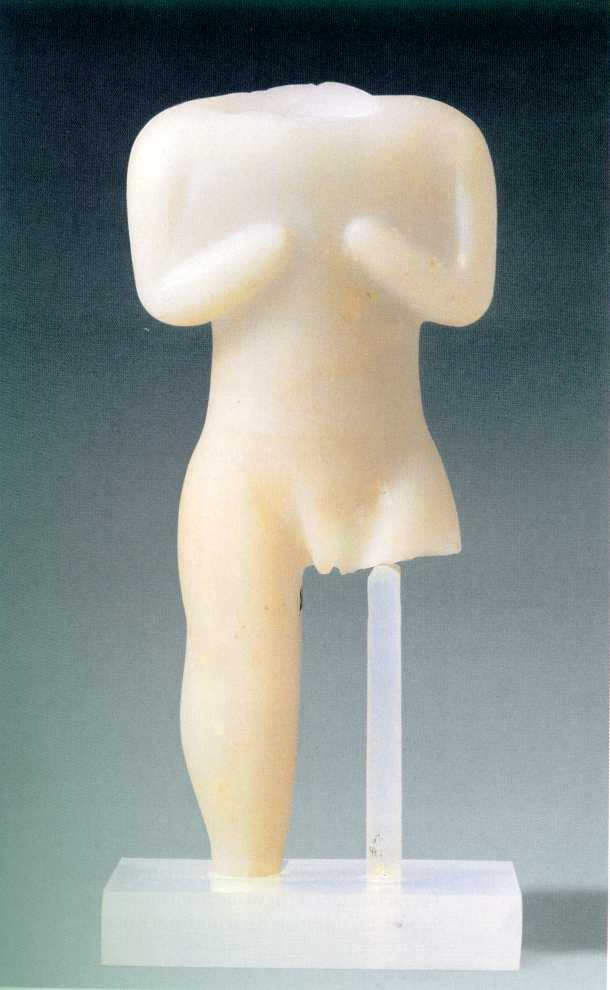

Significant gestures and attitudes vs. insignificant gestures and attitudes. We tried to put face to face images in which the human body serves a message and images in which the gestures are confuse and ridiculous. The attitude of Capitoline Venus (fig.7), found in many of her representations, covering her breasts and pubis, is a transparent manner of symbolizing goddess chastity and femininity. "Psyche at the bath" from the second half of the XIXth century example of ignoring the codes of human representation. The cabaret star attitude that Physche is performing creates an unnatural, forced attitude, empty of signification contracting the mythic theme. The same contradiction appears in figure 10. St. Francis is not preaching to the birds, but gives a hilarious character to the image by his chaotic gestures. He "helps" the image to fall into superficiality. We remark the unjustified presence of the hunch (back) that has a negative meaning. Fig. 9 presents St.Francisc commending, ordering. We found a clear similarity between his attitude and those of roman emperors' statues manifesting their power and the same meaning. Invested with power, the character rises his right hand in order to impose. Fig.11 shows a snapshot. The attitude, the gestures "immortalized" like that are ridiculous and petty, composing a trivial image. We see another snapshot in fig.12. But a snapshot with deep implications and a complex casting. We will resume our comment to the figure in the front plan. Reading the fortune in the palm appears here like a trifle of prophecies of St. John the Baptist. Strangely, the fortuneteller turns the head from the client and has his eyes covered. In this way his figure becomes the symbol of all those that don't believe the Baptist's prophecies (photon telling) being hidden, at the same time (the turning of the back and the hidden eyes).

Annex 4

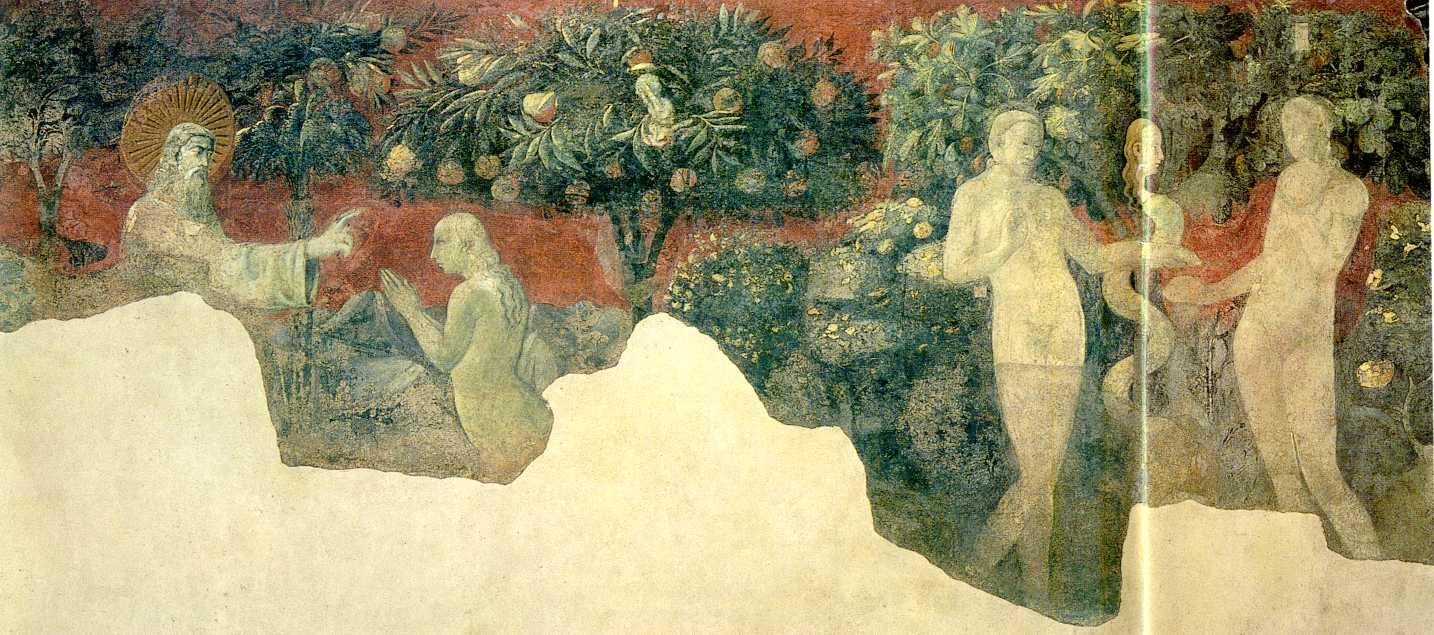

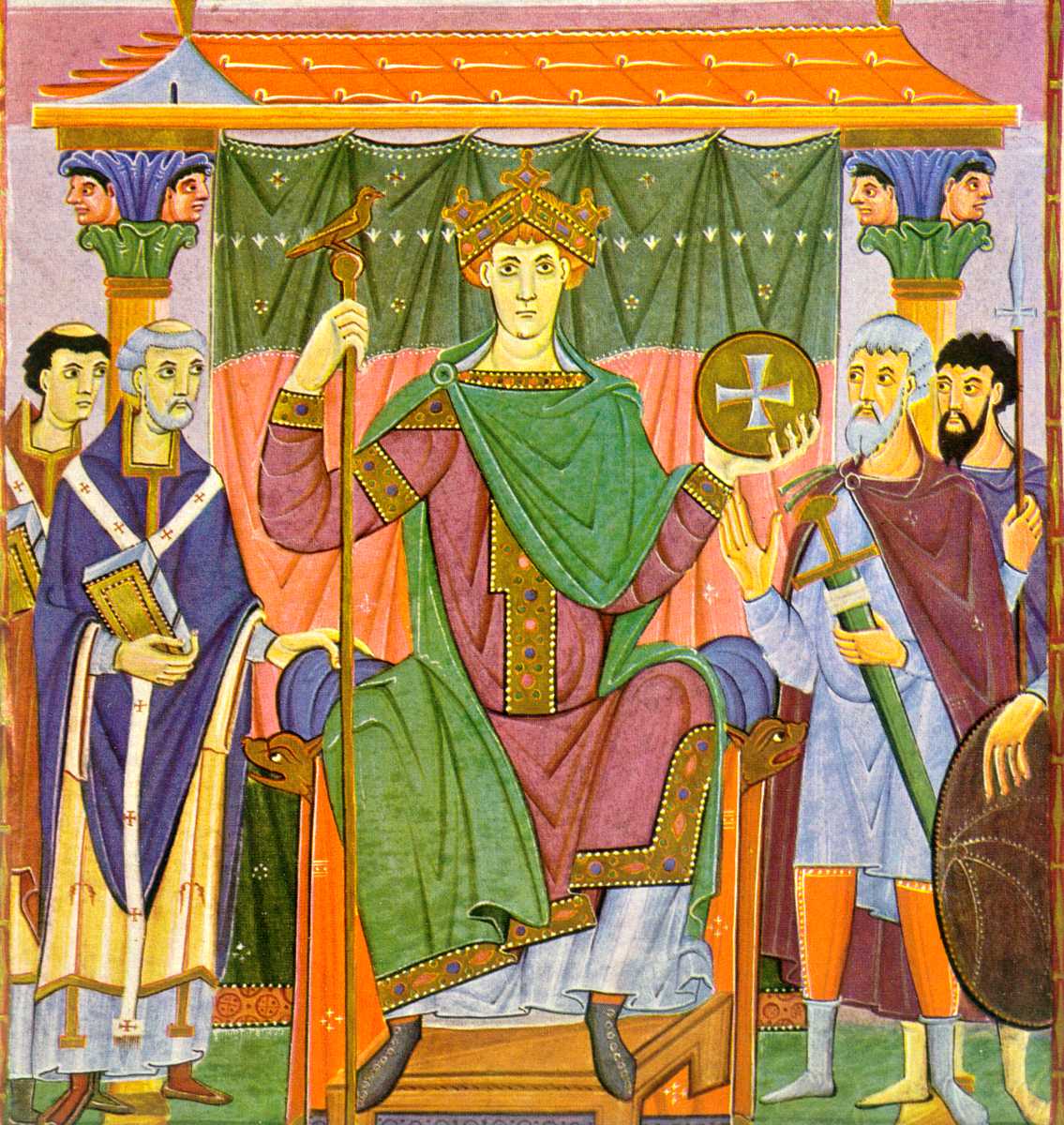

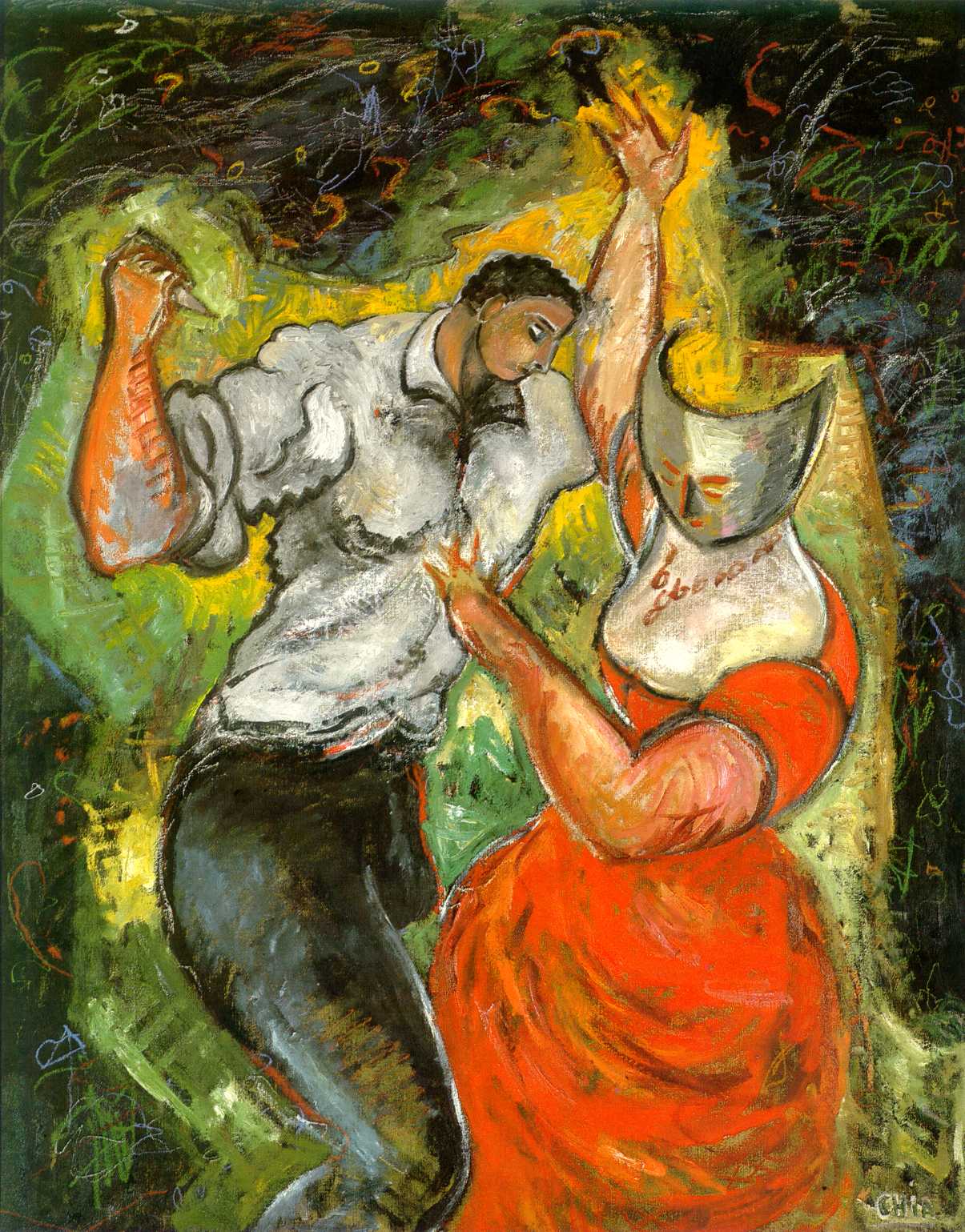

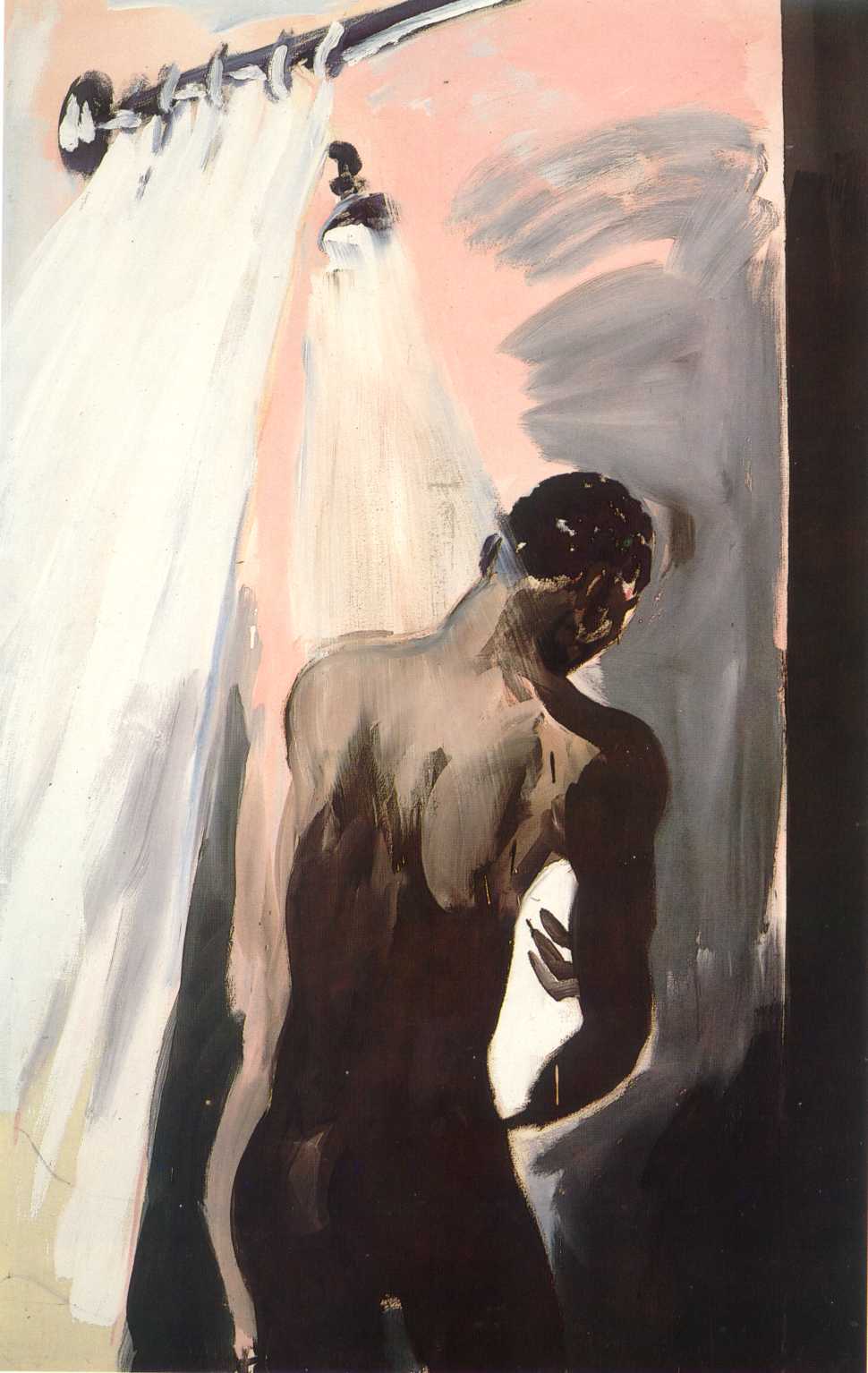

We have already spoke about the meanings of the gesture in fig.13. We met it again in fig 14, and partially in fig.15 with almost the same signification. In fig.14 the figure is no longer invested with power, but is the power itself. God is rising his hand over Eve giving her energy. It is remarkable that the hand of God is visibly larger than normal, underling the action. In fig.15 we find the action's rigidity. Any explanation that puts this under the artist's ignorance is false. It is, in fact correspondent to the statue of the character. We can observe the same uncomfortable and rigid posture in the representations of the Egyptian Pharaohs. The rigidity of the back, the eyes fixed straight ahead, are signs of power and integrity too. The emperor Othon the III rd seats sticky on his throne in fig. 16. A little gesture attracts here our attention: the clergyman on the right holds his hand on the throne. For the emperor this means that his empire and his power are based and sustained on and by the Church. The hand on the head, the arms crossed on the chest (fig. 17), indicate us that we are witnessing a consecration ritual. The blessing is accepted and confirmed by the witnesses, which adopt similar attitudes. Fig. 18 and 19 concerns the same subject: the love and the union of the bride and the groom. We can easily connect the attitudes of the two brides and that of the Capitoline Venus (fig. 7): all three gestures have the same meaning. So do the gestures of the two grooms. Both of them hold the chest of the woman. The chest is the home of the heart, the center, the life, the essence. The breast represents the source of food for life, so the male hand on it confirms its importance.

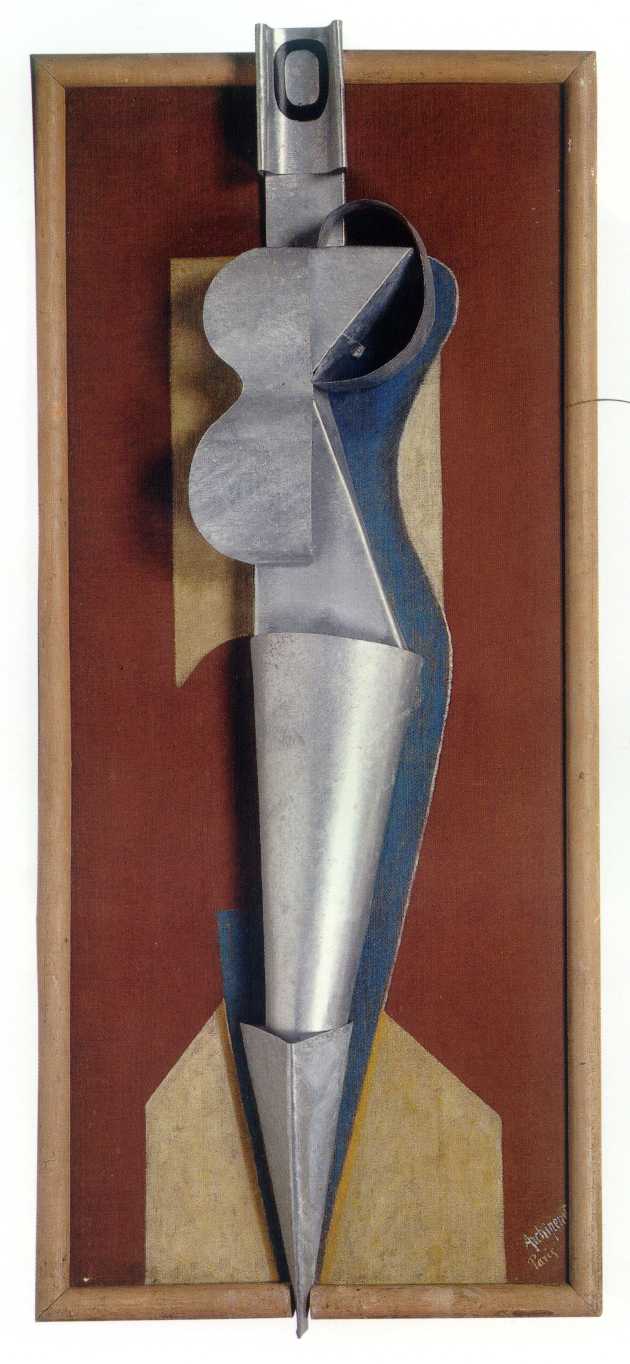

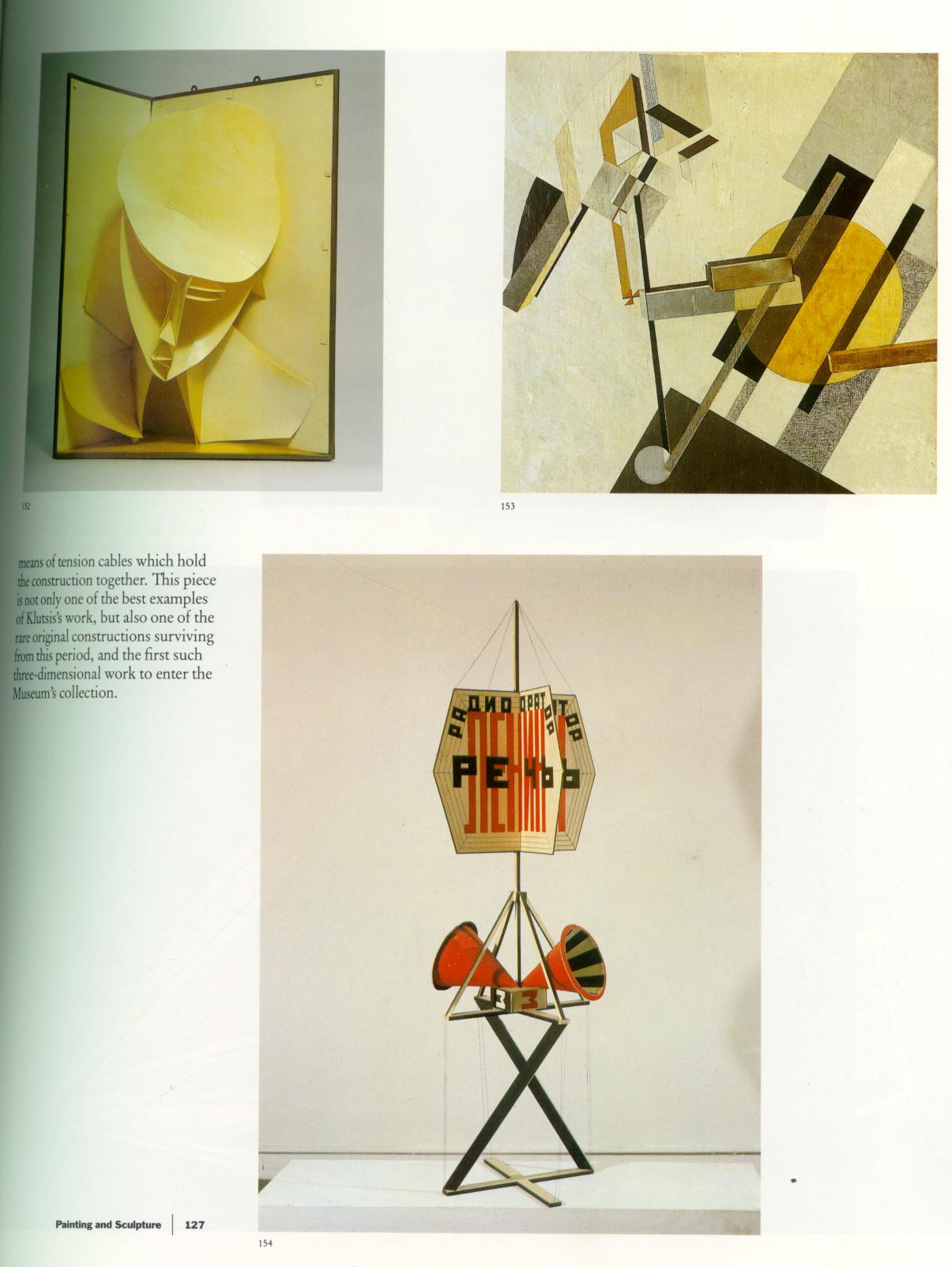

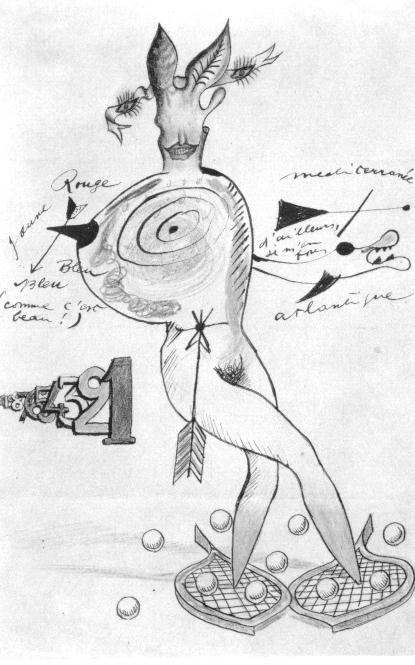

"Les annees folles" and the School of Paris have brought this craziness in the field of the visual arts. But, as we have already shown, the result of such a revolution is chaos and the lack of available criteria. It is very instructive to watch how the most eccentric and most original experiments and formulas become, in just few decades, old and common. In our brief analysis, we have noticed that the authentic formulas that transmit the essences of the human spirit, are everlasting. Works like those in fig. 20 and 21, were at their time the top of the hill. Now they seem to us flat and they don't communicate many things. The mixture of materials, the stylized forms, up to the destruction, lead to a result that does not exist from the significance point of view. We may notice that the main and almost only goal of the modern art is innovation, disregarding that during one lifetime one cannot elaborate and develop a coherent system of representation. The real systems that we are talking about are the result of many centuries of artistic, philosophic, theological and continuous experience. Fig. 22 brings us one of the jokes of the surrealist artists: "Le Cadavre Exquis More artists were drawing on the same sheet of paper, each one continuing at random the work of the previous artist. We look and all we can say is: no comment. If the things may be interesting from the artistic point of view, from that of our analysis this is another proof of placing the human body in a field of ignorance and non-interest.

Fig. 20 - Alexandre Archipenko, "Woman" - France, 1920 |

Fig. 21 - Naum Gabo, "Head of a woman" - Russia, cca. 1917 |

Fig. 22 - Y. Tanguy, J. Miro, M. Morise, M. Ray, "Cadavre exquis" - France, 1926 |

|

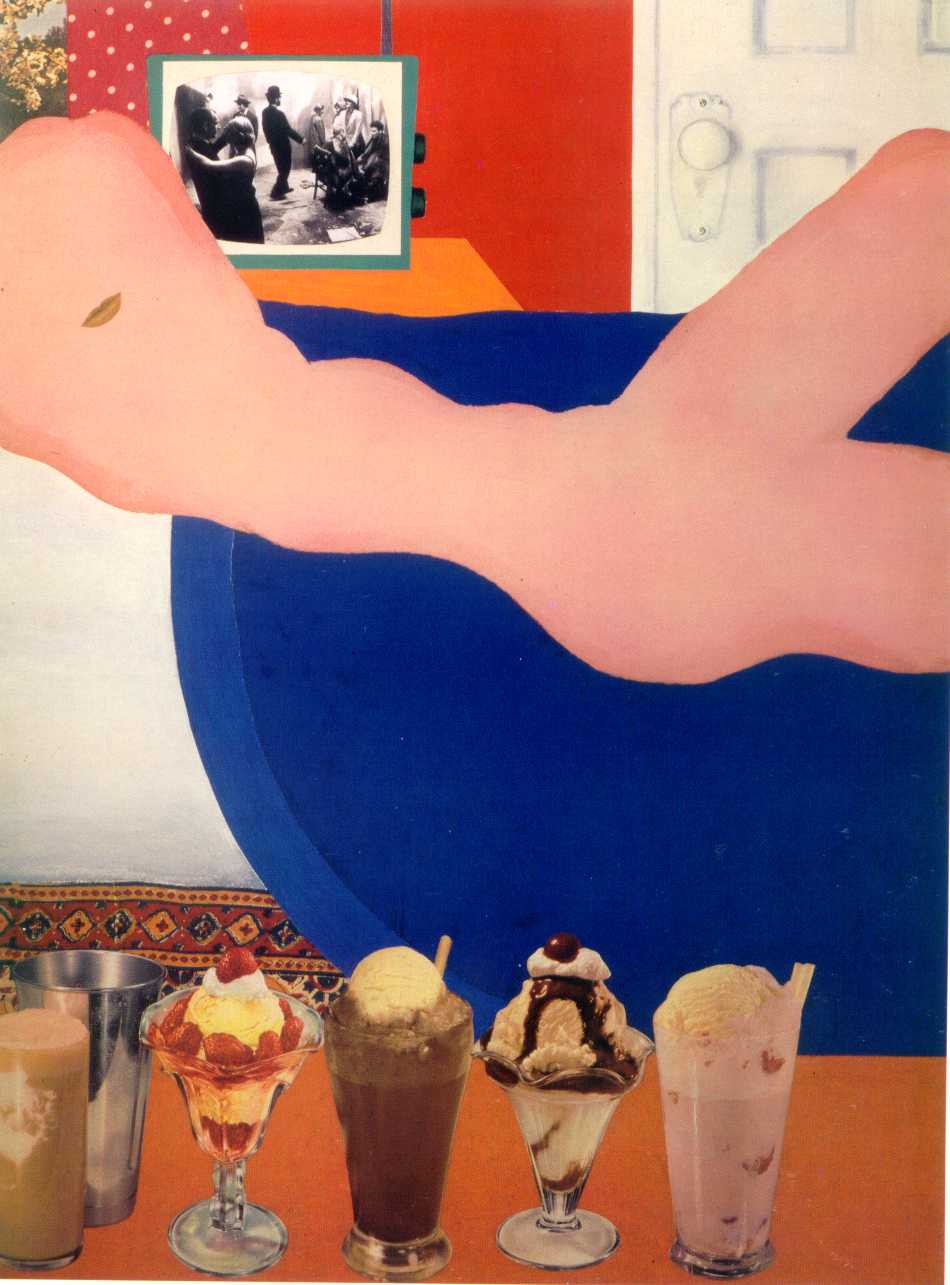

We have already mentioned the dilution of the significance of the human body. Pop-Art offers us a completely flat image of the human being. The portraits that Andy Warhol (fig.23) serializes tirranicaly lead to the destruction of the identity. All three images present the body as a consumable object, nothing different from an ordinary commercial object, as lip-stick, nail-polish (fig.24) or ice-cream (fig.25).

Fig.23 - Andy Warhol, "Marilyn" - USA, nondated |

Fig.24 - James Rosenquist, "Study of Marilyn" - USA, 1962 |

Fig. 25 - Tom Wesselman, "Great american nude" - USA, 1962 |

|

Annex 7

Here are five works of the 80s. The creation of the last two decades distinguish themselves by the lack more and more acute of the concept and of plastic value. Unfortunately, images like those in fig. 26, 27 28, 29, 30 "reveal" to us the ignorance of the image-makers. There will always be a need of the man to see images in which he can recognize his universe. Under these conditions, a clarifying of the terms, a proper reading of the codes, a re-evaluation of the systems is even more indispensable.